POLICY IMPLEMENTATION

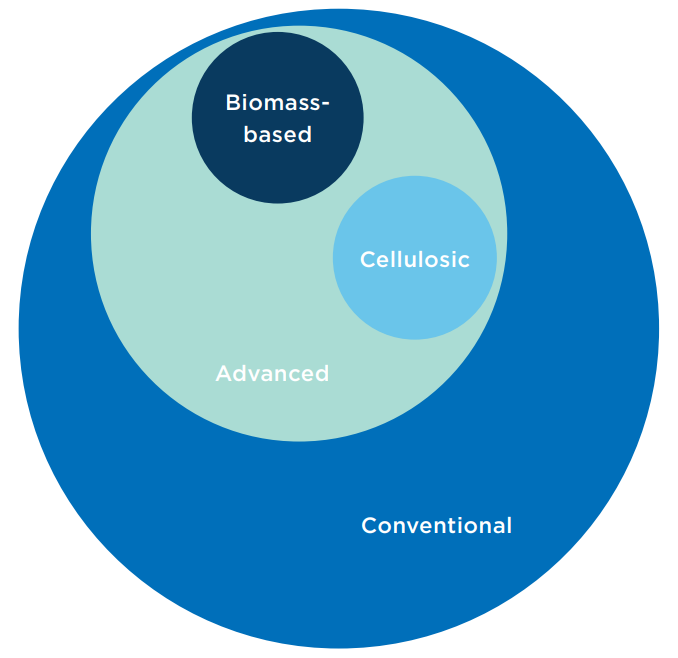

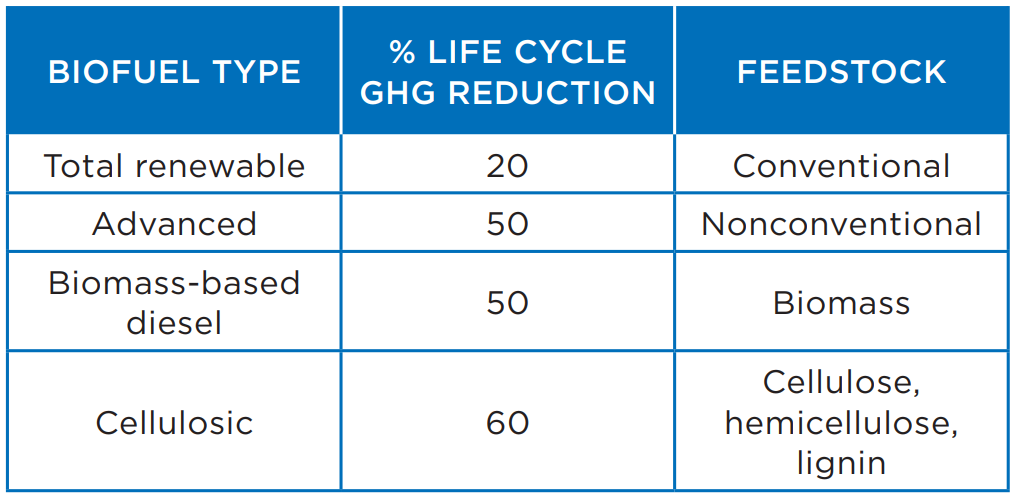

Congress had many motives for creating the RFS in 2005. Among them was the desire to pursue energy security by creating a source of domestically produced transportation fuel. This bipartisan policy also sought to strengthen rural economies, protect the environment and provide resources for an emerging energy economy. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 was expanded upon by the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) in 2007, which increased annual volume requirements; added volume requirements based on biofuel category/GHG emission accounting; expanded the definition of cellulosic fuel; and expanded the EPA’s waiver authority to lower RFS volumes.

Waivers

The 2007 statute was intended to be a “market forcing policy” by creating demand for renewable fuels, specifically biomass-based diesel and cellulosic fuel. The rate at which cellulosic biofuel production was scaled up year over year in the EISA was a premature bet on unproven technology. This aggressive target was established before commercial viability had been proven, when these fuels had only been produced in a lab. Because the technology was unproven, Congress also included the ability to create waivers if cellulosic supply did not expand at pace with the policy’s targets. The EPA can partially or completely waive EISA cellulosic biofuel volume requirements — or requirements for any other specific category of biofuel — if it can be proven that severe economic or environmental harm will result from implementing the volume mandates, or if inadequate domestic supply can be demonstrated.

Another part of the EISA mandate, commonly referred to as the “reset provision,” requires the modification of applicable volumes under certain circumstances, meaning the EPA can change current (as well as projected) volumes for the rest of the statute duration until 2022. This provision is triggered when either the cellulosic biofuel mandate or biomass-based diesel mandate are decreased by at least 20% for two years in a row or 50% in a single year. However, the statute does not include a detailed methodology to determine the new volumetric requirements. This section of the statute took effect in 2016 and has been controversial for biofuel producers and obligated parties alike.

Additionally, the statute provides the EPA with the ability to issue small refinery exemptions, which should not be confused with waivers. To qualify as a small refinery, a facility’s crude oil production must be less than 75,000 barrels per day (BPD). These exemptions are allowed when small refineries can demonstrate “disproportionate economic hardship” would be experienced while trying to fulfill their RVOs. These exemptions, once granted, can be extended. The key to exercising the exemption policy is that it must be granted in the first place, not just assumed by a refinery producing less than 75,000 bpd.

Implications

Among the waivers and exemptions outlined in the statute, two have become the subject of fierce debate. The cellulosic biofuels waiver has been a consistent part of the program ever since cellulosic biofuel was singled out for aggressive commercial expansion in 2007. Originally, Congress projected that the production of this biofuel would be able to climb from 100 million gallons in 2010 to 16 billion gallons in 2022. This projection has been the subject of much scrutiny, as the viability of commercial production was debatable in 2007 and has yet to be proven even as of 2020.

Commercial cellulosic fuel was not produced until 2012, when approximately 20,000 gallons qualified for RINs. The company producing the fuel went out of business a year later. It was not until 2014 that four additional companies produced another 725,000 gallons of cellulosic biofuel. Production reached 2.2 million gallons in 2015, 3.8 million in 2016, and 10 million in 2017. Despite the significant gain in volumetric production, these numbers fall far short of both the nameplate capacity for all four plants (cumulatively 88 million gallons), as well as the EISA’s original mandate of 5.5 billion gallons by 2017. The EPA has had to lower the mandate by approximately 95% to 99% since cellulosic fuels volume obligations began. Despite federally backed loan guarantees and large subsidies, all the original cellulosic biofuel-producing plants have been sold or gone out of business. Without major technological advances, fuel from cellulosic sources will not ascend to the heights hoped for by Congress.

The drastic difference between the EISA projections and actual volumes has called into question the methodology Congress utilized to create the original standard. Subsequent EPA volume projections, created in response to waiver requests, have also come under scrutiny because of a perceived lack of technology neutrality and continued inaccuracy. These necessary waiver provisions and exemptions give the EPA the flexibility required to establish RVOs that are attainable by obligated parties. However, these waivers have also undermined many aspects of the RFS program. The shifting volumetric requirements have eroded the trust of many interested parties. The increased risk associated with these kinds of investments makes them far less appealing, as they are based on a shifting foundation.

In addition, waiver decision deadlines have been missed repeatedly. These decisions have taken much longer than stipulated in the statute, leaving obligated parties in limbo.