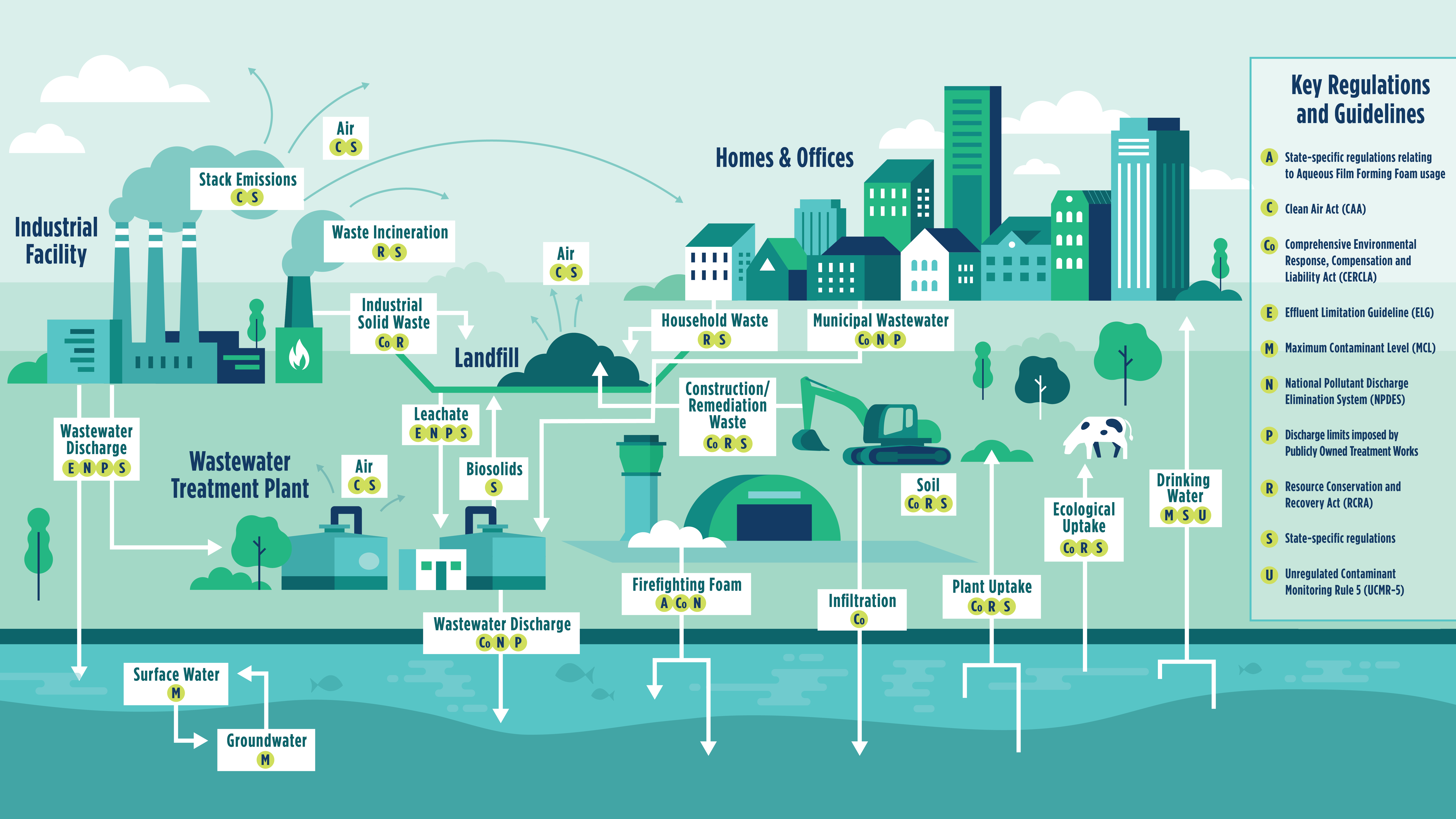

One of the most anticipated federal environmental regulations in recent history is now just one step away from final enactment. The proposed rule designates several widely used man-made chemicals — perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and several other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). That designation, along with proposed national drinking water standards, will pave the way for enforcement actions.

PFOS and PFOA are among the most widely studied PFAS, the “forever chemicals” found in everything from carpets and nonstick cookware to firefighting foam. Known for their toxicity and ability to accumulate in the environment, PFAS break down very slowly over time and are shown to pose health concerns for humans and animals.

By designating these PFAS and their precursors as hazardous substances, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is signaling its intent to increase the frequency of enforcement actions requiring PFAS-contaminated site remediation under CERCLA.

Since its enactment in 1980, CERCLA has served as the regulatory driver behind the cleanup of hundreds of hazardous-waste sites and accidental releases of pollutants and contaminants into the environment. Also known as the Superfund program, CERCLA gives EPA the power to identify and assign liability to those parties responsible for this contamination to pay for the cleanup of the sites. It will now provide the foundation for federal regulatory programs governing PFAS as well.