Driven by a combination of market, policy and financial factors, utility companies and other generation asset owners are increasingly looking to post-combustion capture of carbon dioxide (CO2) to reduce emissions from their gas-fired fleets.

Combined-cycle power plants are emerging as the primary candidates for a strategic capital investment project like post-combustion carbon capture, due to their high capacity factors and long operational lives. While many capture technologies exist and the industry continues to evolve, most near-term project evaluations are selecting an amine-based system.

Heavy industries have relied upon the core process of amine-based carbon capture for decades to treat refinery gas, prepare natural gas for liquefaction, and purify feedstocks for hydrogen production. The process uses a regenerative liquid solvent to selectively remove CO2 from an industrial gas stream. Once heated, the solvent releases a relatively pure CO2 stream that only requires dehydration prior to compression for offtake or sequestration.

However, integrating an amine-based chemical process into a power generation facility is not a simple equipment upgrade. It is an entirely new commercial and project execution model that requires a fundamentally different mindset. The contracting differences between a combined-cycle project and a carbon capture project are the most pronounced in the following five areas:

- Procurement of the core technology.

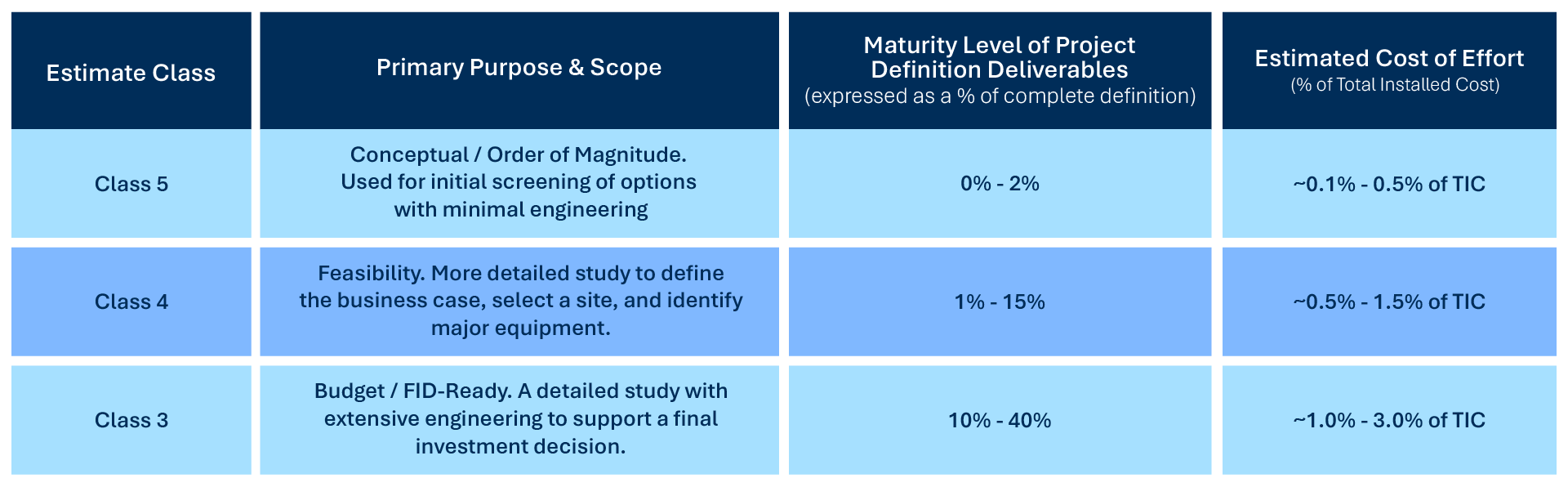

- Cost estimating.

- Structuring of performance guarantees.

- Revenue streams.

- Managing plant operations and maintenance.