Feature | May 16, 2025

Watts Up With the Grid: Enhancing Resilience Under Extreme Weather Conditions

As severe weather events persist, rethinking grid resilience by using renewable energy, new tech and advanced grid hardening is vital to safeguard communities and maintain reliable power.

In the spring of 2025, extreme weather conditions led to widespread power outages, affecting over half a million homes and businesses across five states. The storms, which hit Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky caused extensive damage and highlight the growing vulnerability of traditional grid infrastructure to extreme weather events — a problem that scientists warn will only intensify in coming years.

Our infrastructure’s fragility is a sobering reality. The idea that a single disruption, whether a physical storm or a cyberattack, could lead to a significant crisis is unsettling. However, this also underscores the importance of the critical efforts being made to enhance the reliability and resilience of our electricity supply.

In the face of more severe weather events, power utilities across the nation are racing to fortify their infrastructure against nature’s changing and growing fury. The stakes couldn’t be higher. In recent years, record-breaking hurricanes in coastal states, unprecedented ice storms in the South and Midwest, and catastrophic wildfires in the West have exposed critical vulnerabilities in our aging grid. With climate scientists predicting even more extreme weather ahead, utility executives are abandoning incremental improvements to the grid for more substantial improvements.

“It’s no longer mostly about recovery after the fact and operating from a reactive posture. Now, it’s about building power systems that can withstand increasingly severe and unique weather events from the start.”

Keegan Odle, Vice President, Transmission & Distribution, Burns & McDonnell Vice President, Transmission & Distribution, Burns & McDonnell

When the Lights Go Out

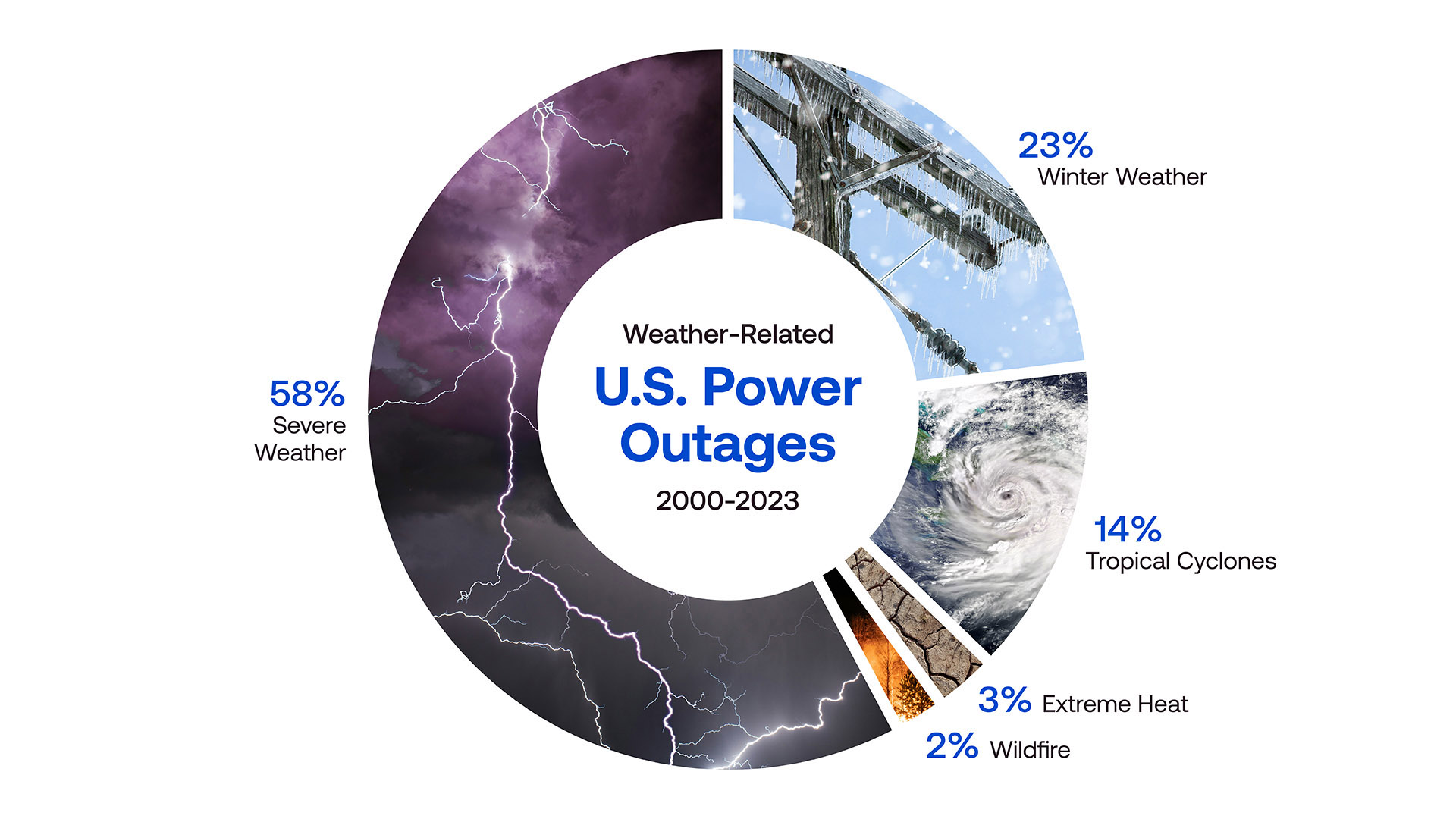

From 2000 to 2023, 80% of major U.S. power outages were weather-related, with the frequency doubling in the last decade compared to the first decade of the century. These outages cost the economy $18 billion to $33 billion annually and affect vulnerable populations disproportionately, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

As extreme weather events and other disasters become more frequent and severe, the need for resilient energy solutions will only grow. Traditional grid infrastructures, built for a more predictable energy landscape, are struggling to adapt to increasing climate hazards, shifting demand patterns and the rise of decentralized energy resources.

Regional differences play a significant role in grid failures. To mitigate region-specific issues, utilities in the West focus on wildfire prevention, implementing technologies that de-energize lines before broken conductors hit the ground. Northeastern utilities, taking lessons from Superstorm Sandy, have elevated critical substations and equipment to be above flood levels. In hurricane-prone southeastern states, utilities have replaced wooden poles with concrete alternatives and increased undergrounding of vulnerable lines. This regional specialization reflects a common challenge: Utilities tend to prioritize protection against threats they have recently experienced — which could leave them vulnerable to changing future dangers.

Source: U.S. Department of Energy

“There’s a recency bias,” Odle says. “The reality is that customers want low-dollar solutions and proof that any spend will deliver results. This, in turn, drives utilities to be more reactive and respond to current and recent situations they’ve faced rather than be able to take a hypothetical and holistic look at changing future conditions.”

One of the more promising strategies for improving grid resilience and preparing for events that have not yet happened involves enhancing interconnectivity of regional transmission systems. From a collective national resiliency perspective, investing in more robust interconnected transmission and distribution systems and having networks more intertwined through architecture could empower resiliency and help prevent entire regions from going without power, allowing power to drive to where it’s needed when hard times hit.

“Utilities are facing a perfect storm of challenges,” says Jeffrey Casey, a Burns & McDonnell transmission and distribution business director. “The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events is straining aging infrastructure. At the same time, after years of flat or declining demand, electricity usage is now projected to grow 1%-2% annually for the foreseeable future. These, among other business-as-usual factors, can overwhelm systems and processes not built for this kind of pressure.”

The U.S. consumes 4,000 terawatt hours (TWh) a year, making it one of the largest and most complex collections of electricity grids on the globe — and a system exposed to some of the world’s harshest conditions, given the country’s varied climate zones.

Casey attributes projected power demand growth to three key factors: data center expansion, the reshoring of manufacturing, and widespread electrification. He acknowledges that during his 16 years in the industry, there has been almost no load growth in the aggregate; in some areas of the U.S., the growth actually has been negative.

But even if the U.S. power industry were to grow only 2% a year over the next three decades, Casey says, the change would be incremental. The country would need to nearly double power supply resources and the size of the grid — essentially building another grid on top of the one that already exists or completely rethinking how to repurpose and use the current infrastructure.

And the grid won’t simply be required to grow; it’s also going to be stress-tested, in real time, by climate volatility. Adding even more risk would be falling severely behind on supply when it would be required the most.

“To think we’re going to double capacity in three decades is daunting,” Casey says. “Even if the estimated projections are half wrong: where will the materials come from? Where will the labor come from to engineer and construct the infrastructure? And how will we keep it all safe and reliable when severe weather strikes? We need to be planning for this now.”

Dealing With Cybersecurity Threats to Resilience

Beyond weather, threats to grid infrastructure also come from malicious actors. Foreign governments and other adversaries are increasingly targeting grid infrastructure through sophisticated cyberattacks on American companies, particularly electric utilities.

In response, utilities are investing heavily in both physical and cybersecurity measures to protect critical infrastructure. Without these investments, utilities risk being unprepared for potential attacks, which could lead to prolonged power outages, economic disruption and compromised public safety. The consequences of inadequate preparation could be catastrophic, affecting millions of people and critical services such as hospitals, emergency response and communication networks.

“Cyberattacks from nation-state actors have the potential to cause widespread power outages on the scale of any storm,” Casey warns. “Utilities are investing strategically to prevent attacks that could compromise the reliability of the grid. They are building enhancements in hardening high-risk assets, improving surveillance to prevent physical attacks and deploying state-of-the-art advanced technology throughout their networks prevent cyberattacks and, ultimately, to strengthen the grid.”

Strategies for Resilient Grid Operations

No matter what part of the country a utility serves, modernizing the grid to improve resiliency for the future involves more than repairing downed lines after a storm; it means building a smarter, more flexible system that can anticipate, absorb and recover from disruptions quickly. While grid hardening requires significant upfront investment, economics favor preparation.

As more severe weather events occur, the costs of being ill-prepared continue to rise. As a result, regulatory frameworks are evolving to incentivize investments in prevention, recognizing that it is ultimately more cost-effective than recovery. Many public utility commissions, for instance, now allow companies to recover costs associated with hardening efforts through rate adjustments.

Utilities can adopt several strategies to enhance grid resilience in the face of severe weather events. Key ones include:

- Renewable energy: Solar and wind power offer decentralized, sustainable alternatives to traditional sources. These renewable energy sources can fortify the grid by providing localized power generation, independent of vulnerable transmission networks and fuel deliveries. Flexible energy solutions combining renewables, storage systems and smart technologies can help with fluctuations in electricity demand and supply during severe weather. For instance, battery storage can store excess solar power, diversifying energy supply and reducing dependence on centralized power plants.

- Underground electric solutions: Relocating overhead power lines underground shields infrastructure from high winds, ice and falling trees, reducing storm-related outages. Implementing underground solutions in high-risk areas, especially near essential facilities like hospitals and emergency services, creates resilience hubs. Though installation costs are higher, underground networks perform better in extreme weather, with up to 80% fewer outages. When considering overhead’s ongoing maintenance, vegetation management and rebuilding of infrastructure following major weather events, the installation of underground lines can narrow the ultimate cost differential, often rendering it negligible.

- Microgrids: As small-scale power grids that can operate independently from the main grid, microgrids offer another component of grid resilience, particularly for health and educational campuses. By integrating renewable energy sources and battery storage, microgrids can provide reliable power during extreme weather events. This decentralized approach helps communities maintain essential services and recover more quickly from disruptions.

- Vegetation management: Regularly trimming trees and vegetation near power lines can reduce the risk of outages caused by falling branches during storms. Utilities can implement comprehensive vegetation management programs to preserve reliable power delivery. Vegetation management often includes regular inspections and the use of advanced mapping technologies to identify high-risk areas. Additionally, collaboration with local communities can enhance the effectiveness of these efforts.

- Grid hardening: Utilities can invest in hardening the grid by reinforcing transmission and distribution lines, upgrading substations and installing underground cables. Grid hardening involves replacing wooden poles with more durable materials like concrete or steel. It also involves reinforcing key infrastructure components such as elevating substations and transformers to prevent flooding and explosions and installing advanced monitoring systems to detect and respond to issues quicker.

An outstanding example of grid resilience strategies that work are on display in the Riazzi Substation, for which Burns & McDonnell handled integrated engineer-procure-construct (EPC) services. This gas-insulated switchgear substation is a part of Duquesne Light Company’s system. The facility — in the heart of Pittsburgh near two university campuses and growing tech, financial and medical industries — relieved potential system overloads, provided a more centralized supply to nearby load centers, and boosted system reliability and resilience.

Harnessing AI and Technology for Resilience

Utilities are increasingly relying on smart grid technologies to enhance storm preparedness and response. Advanced distribution management systems offer real-time visibility into energy consumption and grid conditions, enabling operators to isolate issues, reroute power around damaged sections, and better manage supply and demand during extreme weather events.

Related Content

Article

Streamline the Utility Facility Rating Process With FaciliRate

The integration of smart grid technologies — including smart inverters, advanced sensors, advanced communication networks and comprehensive data analytics — helps optimize grid performance and resilience by managing electricity flow and preventing overloads. As an example, the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s real-time grid monitoring program provides high-resolution, time-synchronized data to help grid operators manage supply and demand more effectively.

To add to their technology arsenal, many utilities, like water utilities, use artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for tasks like sewer pipe defect identification, criticality scoring, lead service line targeting and treatment process optimization. The same can be done for the electric grid. One promising advancement is using AI to automate storm response. AI systems can analyze weather forecasts, historical outage data and grid configurations to predict areas most likely to experience problems. This allows utilities to pre-position crews and equipment before storms hit, dramatically reducing restoration times.

Technology that helps monitor the grid in real time, like FaciliRate — developed by Burns & McDonnell to optimize grid performance amid changing weather conditions — can make a difference as storms roll through.

“The combination of physical hardening and intelligent systems like FaciliRate creates multiple layers of resilience,” says Brian Rutherford, a transmission and distribution technical consultant at Burns & McDonnell. “When severe weather does cause damage, these technologies help us restore power more quickly and efficiently.”

In particular, he’s excited about tech advances that combine communications and power. Meta’s Bombyx robot automates the deployment of fiber-optic cables on power lines, cutting down on time, cost and labor. This new robotic innovation hardens the power lines with the added benefit that fiber can carry more data. Bombyx navigates power lines, identifies obstacles and wraps cables around them, making it ideal for areas where underground installation is challenging or costly. The robot operates without causing power outages and requires minimal human intervention.

In Rutherford’s world, it is not hard to imagine a future where designs are completed by AI, meticulously checked by qualified designers and engineers, and then seamlessly pushed to automated robotic construction systems on jobsites. Utility repair could be as simple as deploying a drone to a precise GPS location to reconnect a conductor, reducing the need for crew deployments and speeding up grid restoration. These advancements have the potential to empower new levels of operational resiliency and elevate grid efficiency, as long as utilities remain diligent about designing the safest and most reliable systems possible.

“The integration of automation and artificial intelligence is transforming grid management and enabling more efficient and resilient designs,” Rutherford says. “I think what we’ll see happen is more creativity out of people, in the sense that AI may be able to help kick out more design options, allowing people more time to find new ways of constructing systems to be more efficient — for example, using 20% fewer materials or having a significantly reduced carbon impact.”

As utilities deploy more sensors and monitoring systems, the focus is shifting from data collection to enlightened knowledge applications. Rutherford emphasizes that while data was the commodity of yesterday, today’s challenge is knowing how to use it effectively to avoid wasted potential: “We have the systems and networks to capture and transmit data, but as future energy grids generate more power, the key will be collecting, interpreting and utilizing the right data to maximize capacity efficiently and cost-effectively. Harnessing data smartly will be crucial for optimizing tomorrow’s energy landscape.”

Forecasting the Grid’s Future

Building true grid resiliency requires a multilayered approach: using strategic undergrounding, advanced materials and innovative construction methods to modernize aging infrastructure, implementing smart technologies that can detect and respond to disruptions quickly, establishing robust communication systems, and developing contingency plans for even the most unlikely of scenarios.

“While dependence on electricity continues to grow in an electrified economy, the grid of the future will look quite different from what we’ve known,” Odle says. “But one thing will remain constant: our company’s commitment to helping our clients provide safe, cost-effective and reliable power to the communities they serve, regardless of what is thrown our way, natural or human-made.”What’s New in Trenchless Technology?

Developers looking to harden their transmission lines often go underground — turning to horizontal directional drilling (HDD), the most popular approach for running lines under roads, creeks or even assets in urban areas.

“Interestingly, innovation is happening in the underground space,” says Kerby Primm, an associate technical consultant at Burns & McDonnell. “Underground lines are now seen as a necessary investment, altering utilities’ long-term planning and capital allocation. Trenchless technology is undeniably valuable for enhancing grid resiliency, reducing environmental impact, and maintaining aesthetic values in urban and suburban areas. Seeing the innovation taking place makes this an exciting time.”

Undergrounding methods gaining traction include:

- Pipe jacking methods like advanced trenchless microtunneling. These methods involve creating a pit at the required depth and pushing pipe segments through the ground using a jacking mechanism. Microtunneling is suitable for larger-diameter pipes and longer distances, often used in urban settings where space is limited or ground conditions are variable. Jack-and-bore, also known as horizontal auger bore, is typically used for shorter distances and smaller diameters. Pipe jacking methods are essential for installing casing pipe for high-voltage cables in areas inaccessible to open cut or overhead installations.

- Direct steerable pipe thrust (DSPT), also known as Direct Pipe, is a relatively newer technology that combines elements of HDD and microtunneling. It uses a microtunnel boring machine (MTBM) with steerability similar to HDD, allowing for installation of pipes in challenging environments. DSPT is particularly effective in areas with boulders/cobbles or expansive soils, providing a robust solution for underground installations.

- E-Power Pipe is another new technology, one designed specifically for installing high-voltage direct current (HVDC) cables. This method involves shallow pit-to-pit installations and can cover distances up to 2 kilometers. E-Power Pipe offers a cost-effective alternative to traditional open-cut methods, making it a promising technology for future power transmission projects.

- GeoNex horizontal drilling utilizes a hammer mechanism at the front of the casing pipe, pulling the pipe through dense rock formations. This technology is ideal for areas with glacial till or cobbles, where traditional methods may struggle. GeoNex provides a reliable solution for installing casing pipes under railroads and interstates.

“The upfront cost using the new technology may be slightly higher, but the long-term, long-lasting benefits of trenchless installations far outweigh the initial investment,” Primm says. “By minimizing surface disruption and providing durable underground solutions, trenchless technology is paving the way for a more resilient and efficient grid.”

Thought Leaders

Keegan Odle

Vice President, Transmission & Distribution

Burns & McDonnell

Jeff Casey

Business Director, Transmission & Distribution

Burns & McDonnell

Brian Rutherford

Associate Technical Consultant, Transmission & Distribution

Burns & McDonnell

Kerby Primm

Associate Technical Consultant, Transmission & Distribution

Burns & McDonnell

Related Content

Power

Transforming Power With Integrated Solutions

White Paper

Importance and Benefits of Going Beneath the Surface

Case Study

Duquesne Light Company Prepares for the Future in Pittsburgh’s Urban Core

.png)